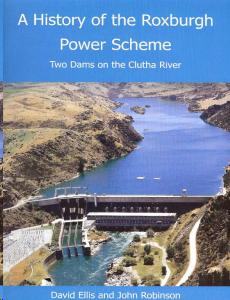

A History of the Roxburgh Power Scheme

A History of the Roxburgh Power Scheme

- Two Dams on the Clutha RiverDavid Ellis and John Robinson 2012 D G Ellis, Nelson. 241 pp. ISBN 978-0-473-20922-3

There is a review here: http://www.ipenz.org.nz/nzsold/Roxburgh/Review.pdf

The book can be ordered at http://www.ipenz.org.nz/nzsold/Roxburgh/OrderBook.htm

Review

This is a POP page.

|

Two dams? – Well the clue is in the power scheme title, the second dam is the lake regulating dam built at Lake Hawea as part of the development. Both authors worked on the scheme as young engineers, so some of the recollections are personal. Ellis’s other book on Central Otago dams has also been reviewed here.

There is a lot more that happens in building a dam than appears on the surface of the finished structure and this makes it clear what was involved. It is not just the physical side either. The social issues involved with the largely immigrant work force and their accompanying families are set out as well. Roxburgh was in its day the largest power project ever started and it had lessons and consequences for the succeeding South Island power projects.

The authors cover a lot of technical ground. Generally this is made very clear – well at least to an engineer, but there are a couple of reminiscences included where the references to technology are abbreviated – no doubt they are meaningful to the originators but they could have done with some more explanation from the authors.

The organisation and contractual side is interesting too. The project proceeded through a number of organisational changes in the electricity and engineering agencies but these do not seem to have been a barrier. The work was started by the Public Works come Ministry of Works and they continued to have a major role as designers, inspectors and builders of part of the work. The new electricity department too had a major role in delivering the works, not just in being the client. The incoming National Government of 1949 had a philosophical view that much of the work should be contracted out and the public construction organisation agreed, as they could not find the resources to meet progress targets that were slipping. They were already heavily committed in the North Island.

The resulting contract was let to a consortium lead by British contractor Cubitts but it was not a success – they had a lot of resources but not enough of the right ones for a dam and slow progress remained. The target price contract was problematic too as there was not a rigorous methodology for progress payments. There was an inevitable crisis. Extraordinarily the Prime Minister called a meeting at his holiday home and invited an outside party, Downers to attend. The swift outcome was a revised contracting organisation with the former parties now lead by Arnold Downer, termination of the target price arrangement and its replacement by a scheduled rate contract. Many staff changes resulted, but so did progress. A principal today would not be happy at the lack of price tension in arriving at the rates schedule. One can only think that the formidable experience of the Ministry of Works had a large role in moderating this.

Seventeen workers died in the project, a number not commented on but it would be inconceivable today. Hard hats for instance, only came into use later in the project.

Perhaps understandably the off-site works get less attention and it is not the best resource for discovering what other features from the construction remain in the landscape, but a visit to Google Earth shows there are some. An industrial archaeologist will find this book a vital background on the project but not a great guide as to what was where away from the dam. I loved the story about the river gravel aggregate plant where the fine material was put through a riffle to recover gold but this was after any nuggets had already been screened off – they went into to the dam concrete.

A few grizzles – while it is very fully illustrated some of the photos and diagrams are reproduced at far too small a scale to be readable – fewer and larger would have been better. The release flows in the Lake Hawea control structure have to be supercritical flow – the text says not but then inconsistently talks about the stilling basin structure at the outlet end.

This reviewer remembers being taken as a boy to the public viewing point to view the construction – a diversion on holiday trips to Central Otago from Dunedin. In memory the cableways handling much of the lifting were the most impressive feature. The Dunedin papers gave much space to the scheme and the quite frequent power cuts were a reminder of its need. The challenging diversion of the river was on the movie news. Your reviewer went on to work on the design of three dam projects and the construction of two, so – what you do with your kids on holidays is not inconsequential.