Difference between revisions of "Maori Gardening"

(→Footnotes) |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polynesians/ Polynesian ancestors] of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Māori/ Maori] brought with them long-established gardening traditions and techniques when they settled [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Zealand/ New Zealand] in about AD 1250–1300. There is archaeological evidence of the continuation of Polynesian gardening practices in New Zealand and adaptations of gardening techniques to suit the local environment. These [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultigen/ cultigens] were important sources of sustenance for the Maori alongside fishing and gathering, and played a major role in exchange relations with other groups. Gardening provided essential carbohydrates when there was little other wild food, and was supplemented by gathering and fishing. Later, introduced European cultigens such as the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potato/ potato] were incorporated into Maori agriculture and exchange systems. In the first half of the 19th century, the sale of vegetables formed the basis of the Maori commercial economy. | The [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polynesians/ Polynesian ancestors] of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Māori/ Maori] brought with them long-established gardening traditions and techniques when they settled [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Zealand/ New Zealand] in about AD 1250–1300. There is archaeological evidence of the continuation of Polynesian gardening practices in New Zealand and adaptations of gardening techniques to suit the local environment. These [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultigen/ cultigens] were important sources of sustenance for the Maori alongside fishing and gathering, and played a major role in exchange relations with other groups. Gardening provided essential carbohydrates when there was little other wild food, and was supplemented by gathering and fishing. Later, introduced European cultigens such as the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potato/ potato] were incorporated into Maori agriculture and exchange systems. In the first half of the 19th century, the sale of vegetables formed the basis of the Maori commercial economy. | ||

| − | Though much archaeological evidence of gardening exists, the extent to which cultivated crops provided a staple food for the Maori has been questioned | + | Though much archaeological evidence of gardening exists, the extent to which cultivated crops provided a staple food for the Maori has been questioned (Shawcross 1967; Leach 2000). Seasonal crop failures and political unrest resulted in fluctuations in the supply of crops. Cultivated food was not a consistent dietary staple, though it was an important aspect of Maori daily and ceremonial life. |

== Garden Preparation and Characteristics== | == Garden Preparation and Characteristics== | ||

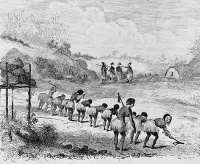

[[Image:Digging_kumara_garden.jpg|thumb|left|200px| Maori women digging land for a kumara garden]] | [[Image:Digging_kumara_garden.jpg|thumb|left|200px| Maori women digging land for a kumara garden]] | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| − | == References == | + | == Notes and References == |

| − | *FUREY, | + | *BEST, E. 1976: Maori agriculture. Government Printer, Wellington. 315 p. |

| − | + | *COLLENSO, W. 1880: On the vegetable food of the ancient New Zealanders before Cook’s visit. Transactions of the New Zealand Institute 13: 3–38. | |

| − | [ | + | *FUREY, L. 2006. [http://www.doc.govt.nz/upload/documents/science-and-technical/sap235.pdf/ Maori gardening: An archaeological perspective]. Wellington, New Zealand: Science and Technical Publishing. |

| − | + | *HORN, H. 1993: Rekamaroa kumara, sand and soil. Archaeology in New Zealand 36: 185–189. | |

| + | *JONES, K.L. 2002. [http://www.doc.govt.nz/upload/documents/science-and-technical/ArchSitesA.pdf/ Caring for archaeological sites: New Zealand guidelines]. Wellington, New Zealand. Department of Conservation. | ||

| + | *LEACH, H.M. 1976: Horticulture in prehistoric New Zealand: an investigation of the function of the stone walls of Palliser Bay. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin. 221 p. | ||

| + | *LEACH, H.M. 1984: 1,000 years of gardening in New Zealand. Reed, Wellington. 157 p. | ||

| + | *LEACH, H.M. 2000: European perceptions of the roles of bracken rhizomes (Pteridium esculentum (Forst. f.) Cockayne) in traditional Maori diet. New Zealand Journal of Archaeology 22 (2000): 31–43. | ||

| + | *SALMOND, A. 1991: Two worlds. First meetings between Maori and Europeans 1642–1772. Viking, Auckland. 477 p. | ||

| + | *SHAWCROSS, K. 1967: Fernroot, and the total scheme of 18th century Maori food production in agricultural areas. Journal of the Polynesian Society 76: 330–352. | ||

[[Category:Gardening]] | [[Category:Gardening]] | ||

Revision as of 14:41, 23 February 2010

Contents

Summary

The Polynesian ancestors of the Maori brought with them long-established gardening traditions and techniques when they settled New Zealand in about AD 1250–1300. There is archaeological evidence of the continuation of Polynesian gardening practices in New Zealand and adaptations of gardening techniques to suit the local environment. These cultigens were important sources of sustenance for the Maori alongside fishing and gathering, and played a major role in exchange relations with other groups. Gardening provided essential carbohydrates when there was little other wild food, and was supplemented by gathering and fishing. Later, introduced European cultigens such as the potato were incorporated into Maori agriculture and exchange systems. In the first half of the 19th century, the sale of vegetables formed the basis of the Maori commercial economy.

Though much archaeological evidence of gardening exists, the extent to which cultivated crops provided a staple food for the Maori has been questioned (Shawcross 1967; Leach 2000). Seasonal crop failures and political unrest resulted in fluctuations in the supply of crops. Cultivated food was not a consistent dietary staple, though it was an important aspect of Maori daily and ceremonial life.

Garden Preparation and Characteristics

Mean temperature and the length of the growing season were the main limitations to the regional distribution of Maori gardening. The higher the minimum soil temperatures, the better the growth and yields. Low soil temperatures in late summer and early autumn affect the viability of tubers and inhibit germination the following year. Historic observations hold that only kumara could be grown in the South Island and southern North Island. While taro was more cold-resistant than yam, neither could be grown south of Poverty Bay or Hawke's Bay.

Following the clearing and burning of shrubs, the ash was collected and spread over the soil. Branches and stones were cleared to the outer edges of the garden and the soil loosened. Heavy clay soils were improved by soil additives. Where light, porous soils were unavailable, these were improved by a layer of sand or gravel. Heavy clay soils were improved by gravel, but were not favored because of the labor-intensive process. Lighter, rich soils were preferable for kumara cultivation, and small amounts of gravel could be used under the plants to protect them from mud and dampness, aerating and warming the soil as well. According to early European accounts, gardens ranged from 1-10 acres, though a garden of 40-50 acres was seen planted around Moturua Island (Salmond 1991: 164, 230). Flat land is too damp for sweet potato cultivation, and sloping, well-draining, north-facing lands were preferred to protect crops from cold south wind. Fences were commonly observed around gardens, serving as either windbreaks of barriers to keep ground-dwelling birds and animals out. Kumara appears to have been planted in gardens separate from other crops, this separation in keeping with the observance of the ritual associated with the planting and harvesting of kumara (Best 1976).

Archaeology of Maori Gardening

Stone Structures Stone rows and walls are the most visible evidence of gardening. Stone structures are found around volcanic cones, old raised beach ridges, weathered fans, and river flats where weathered gravels are exposed or near the surface. Archaeological literature from Eastern and Central Polynesia confirms the use of stone walls in garden plots, and reinforces that such gardening practices, imported into New Zealand, are part of a long tradition in Polynesian agriculture (Leach 1976: 134–144). Stone walls and rows define boundaries of garden complexes, and generally appear in a regular pattern. They are parallel, and have rows at right angles, dividing the gardens into identifiable plots.

Ditches and Channels Ditch and channels are difficult to see and may be severely under-represented archaeological records. Because they are shallow, they are vulnerable to erosion and infilling, and in flat land are easily destroyed by ploughing and intensive land-use practices. Ditches and channels occur in various situations and with various functions according to regions. In some gardens, parallel depressions on slops were intended to function as fences or garden partitions, though they may have served as drains. Ditches in swamp areas of the Northland may have controlled the flow of water from sources such as springs to gardens and served as water diversion systems. Additionally, ditch systems in swamps may have served for trapping eels, fish, and ducks. Several different and overlapping functions are implied from surface evidence.

Garden Soils There are several types of evidence for garden soils, none of which are visible on the surface. Sand and gravel were added to clay soils to improve drainage and texture, and shell, charcoal, and fine pebbles have been identified as well. The most common garden soils have sand or gravel added to the original topsoil. Substantial benefits may have been derived from modifying soils. Modifications to soils could them warmer and better-drained, allowing for a longer growing season. When tested, soil plots near Christchurch were tested for temperature variation. For mixed soils, night-time temperatures in all plots were similar, but the benefits of adding sand and gravel to soil became apparent during the day when the soil reaches a peak of 4°C higher than the unmodified soil (Horn 1993). Soils mixed with charcoal did not reach the maximum surface temperature of other soil mixtures, but retained heat for longer overnight.

Cultigens

Kumara (Sweet potato, Ipomoea batatas) was the most extensively grown Maori cultigen in New Zealand. Unimportant in most of tropical Polynesia--with the exception of Easter Island where it was a principal crop--Kumara may have attained primary crop status in New Zealand due to its faster maturation and greater tolerance of New Zealand's dry and cool climate. Of all the Maori cultigens, kumara is the most tolerant of the widest range of conditions. Temperature is a critical factor in tuber propagation and plant growth. Similarly, low soil temperatures and excessive moisture can lead to rot. Captain James Cook observed kumara grown in rows, on mounds, in a quincuncial pattern. Different varieties were known for specific characteristics, such as sweetness, flavour, the production of large tubers, or high yield. (Leach 1984: 103).

Taro (Colocasia esculenta) was grown primarily for the starchy tuber, though the leaves could also be eaten after cooking. In tropical Polynesia, there is both wetland cultivation using ditches, ponds, and irrigation, and dryland cultivation of taro. Early European accounts mention only the latter in New Zealand(Collenso1880: 8). Taro has higher moisture requirements than kumara and in the wild often grows on the banks of streams or in swampy areas. Taro was not grown on mounds but on carefully leveled surfaces, surrounded by fences or screens to provide shelter from the wind. Taro can be found in the northern half of the North Island as cultivated or wild plants.

Calabash (Lagenaria siceraria) Calabash gourds were grown primarily for the large fruits which were used as containers to store water, oils, and food. Small immature fruits were eaten during the summer before the kumara were harvested. A comparatively long growing season of 6-7 months is required for the fruit to enlarge and mature. Like other crops, calabash is temperature sensitive and grows most favorably when the mean temperature is above 17°C. Calabash requires damp, rich soil and it was often grown near taro plantations.

Notes and References

- BEST, E. 1976: Maori agriculture. Government Printer, Wellington. 315 p.

- COLLENSO, W. 1880: On the vegetable food of the ancient New Zealanders before Cook’s visit. Transactions of the New Zealand Institute 13: 3–38.

- FUREY, L. 2006. Maori gardening: An archaeological perspective. Wellington, New Zealand: Science and Technical Publishing.

- HORN, H. 1993: Rekamaroa kumara, sand and soil. Archaeology in New Zealand 36: 185–189.

- JONES, K.L. 2002. Caring for archaeological sites: New Zealand guidelines. Wellington, New Zealand. Department of Conservation.

- LEACH, H.M. 1976: Horticulture in prehistoric New Zealand: an investigation of the function of the stone walls of Palliser Bay. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin. 221 p.

- LEACH, H.M. 1984: 1,000 years of gardening in New Zealand. Reed, Wellington. 157 p.

- LEACH, H.M. 2000: European perceptions of the roles of bracken rhizomes (Pteridium esculentum (Forst. f.) Cockayne) in traditional Maori diet. New Zealand Journal of Archaeology 22 (2000): 31–43.

- SALMOND, A. 1991: Two worlds. First meetings between Maori and Europeans 1642–1772. Viking, Auckland. 477 p.

- SHAWCROSS, K. 1967: Fernroot, and the total scheme of 18th century Maori food production in agricultural areas. Journal of the Polynesian Society 76: 330–352.