Difference between revisions of "NZ Legislation History"

(New page: {{verify}} {{Ark|date=2002}} History taken from Chapter 2 of Tanner, V. 2002. An Analysis Of Local Authority Implementation Of Legislative Provisions For The Management...) |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 07:23, 1 May 2008

|

The content of this page has not been verified.

|

This is an ARK page.

It represents an important contribution to the Authoritive Repository of Knowledge.

A qualified professional has written this document and proper acknowledgement should be given in referencing this material. In additional the document should only be modified by the original author or approved editor with the permission of the author.

Originally written in 2002.

History taken from Chapter 2 of Tanner, V. 2002. An Analysis Of Local Authority Implementation Of Legislative Provisions For The Management And Protection Of Archaeological Sites. Unpublished thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

HISTORY OF LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENT

Introduction

In order to evaluate the present system of archaeological resource management, identify problems, and suggest solutions this chapter discusses the evolution of legislation and institutions involved in historic heritage management and protection in New Zealand. For the purpose of this chapter it has been necessary to trace the development of historic and cultural heritage legislation rather than provisions for archaeological resource management per se. Legislation that can be applied to archaeological sites is more often implied or interpreted than specifically stated in statute. Provisions that specifically mention archaeological sites have been in existence since the Reserves and Domains Act 1953. However, provisions aimed at the protection of archaeological information have only been included in statute since the Historic Places Amendment Act 1975. To develop an understanding of current local authority roles in historic heritage management it has been necessary to broadly trace the principal Acts leading to the devolution of decision making resulting in the present system of local authority management of resources.

Both the prehistory and colonial history of New Zealand are relatively short in comparison with other parts of the world. It is for this reason that many people fail to value the significance of archaeological sites in New Zealand. However the significance of archaeological sites should not be underestimated. They play an important role as a physical link to the past and they are the source of archaeological information for academic inquiry. More recently archaeological sites have been recognised as a socio-cultural resource because they provide evidence of continuity, they create a sense of place and can be wahi tapu. For these reasons archaeological sites have been recognised in statute. Although archaeological information has been considered in legislation for almost a century, protection of the archaeological resource is relatively new.

At the broadest scale institutional and legislative development in New Zealand reflects change at the global level. Changes in the global economy have required New Zealand to promote itself independently and find means of income other than farming, which predominated prior to the 1970s. This has seen a diversification of the economy often physically expressed in multiform land use. In addition New Zealand and the world has witnessed the continued growth of the tourism industry. Ideologically there has been a shift from the homogenisation of the modernist era to a promotion of difference and celebration of culture characteristic of the post-modern period. New Zealanders recognised the importance of developing a national identity early on in the country’s history. In the past decade it has become evident that this identity must incorporate all of our cultures. Te Papa, the Museum of New Zealand, is testimony to this. Nationally the country has seen the progressive devolution of decision-making. At the local level communities are provided with greater roles in decisions affecting the district in which they live. They also have greater opportunities to create local identities and economies to meet the growing need to promote towns not only for tourism reasons but to create a sense of place. ’From the 1980s onwards […] heritage has become part of a community branding exercise, the creation of a point of differentiation in fostering community pride while luring visitors’ (McLean 2000b:85).

Institutional and legislative development also relate to changes in the discipline of archaeology. Development of the discipline has influenced ideas and perceptions within the institutions involved in the growing historic heritage industry. Archaeological heritage management in New Zealand has taken much longer to become established than the academic discipline. Investigation into the state of archaeological resources and the ways in which they are managed has only become the focus of attention in the past decade. This process is not unique to New Zealand. Cleere (1989:1) mentions that ’the academic discipline of archaeology and the administrative function of archaeological heritage management are twins that have developed at different rates.’ Academic archaeological inquiry in New Zealand has been a part of understanding our history from the early 1900s, first in museums and later by universities. It is only in the last twenty years however, that significant growth has occurred in the historic heritage management sector, increasingly independently of the traditional historic heritage institutions.

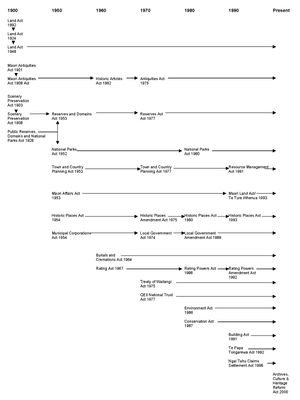

The history of legislation reflects the rapid changes this country has undergone; it reflects the attitudes of a nation trying to develop socially, culturally and economically. It is a reflection of changing global perspectives, particularly in regard to managing the environment. Figure 2.1 schematically organises the development of legislation that was, and still is in some cases, applicable to cultural and historic heritage management in New Zealand. It includes all of the Acts for which historic heritage provisions will be discussed in this and the following chapter. Figure 2.1 demonstrates how past Acts were remodelled into new pieces of legislation and indicates the Acts that are currently in use today. The figure represents the reorganisation rather basically as many provisions of early Acts were repealed or split among several new statutes. The aim is to illustrate the progression of the legislative change that has a relationship to historic and/or cultural heritage management.