Difference between revisions of "NZ Legislation History"

m |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<div style="width: 80%; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; padding: 4px; border: 2px solid #000000; background-color: white; text-align:center;">History taken from Chapter 2 of [[Tanner Vanessa|Tanner, V]]. 2002. An Analysis Of Local Authority Implementation Of Legislative Provisions For The Management And Protection Of Archaeological Sites. Unpublished thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.</div> | <div style="width: 80%; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; padding: 4px; border: 2px solid #000000; background-color: white; text-align:center;">History taken from Chapter 2 of [[Tanner Vanessa|Tanner, V]]. 2002. An Analysis Of Local Authority Implementation Of Legislative Provisions For The Management And Protection Of Archaeological Sites. Unpublished thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.</div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

==HISTORY OF LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENT== | ==HISTORY OF LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENT== | ||

| Line 111: | Line 113: | ||

The second Act of the 1970s still applicable to historic heritage management today is the Reserves Act 1977. This Act makes provision for the acquisition, control, management, maintenance, development and use of reserves. According to the Department of Conservation (1995a:1) the Reserves Act 1977 is <nowiki>’</nowiki>more powerful than registration under the Historic Places Act 1993, or the Resource Management Act 1991 which provides for listing in a District Plan or the issuing of heritage orders.<nowiki>’</nowiki> Section 18 allows for the classifying of a reserve based on its historic merit alone. Under section 18 historic reserves include such places, objects, and natural features, and such things thereon or therein contained as are of historic, archaeological, cultural, educational, and other special interest. Section 58 lists the powers of the Minister and Administering Body in respect to historic reserves. Consistent with the earlier Reserves and Domains Act 1953, landowners are able to set up reserves on private land through application to the Minister of Conservation <nowiki>[</nowiki>s76<nowiki>]</nowiki>. A problem inherent in the Reserves Act 1977 is its focus on the <nowiki>’</nowiki>principal or primary purpose<nowiki>’</nowiki> of a reserve and the implication this creates for the management of reserves. Unfortunately, for this reason, historic values may be compromised in enhancing the primary values of a reserve such as recreation or scenery. The Department of Conservation (1995a:2) provides the example of Bowentown Heads in Tauranga Harbour, classified as a recreation reserve. The top of the pa Te Kura a Maia was damaged through the creation of a car park to cater for its primary purpose of recreation. This Act was administered by the Department of Lands and Survey until the Conservation Act 1987 was implemented at which point it was handed to the DOC who actively manage more than half of the registered reserves in New Zealand. | The second Act of the 1970s still applicable to historic heritage management today is the Reserves Act 1977. This Act makes provision for the acquisition, control, management, maintenance, development and use of reserves. According to the Department of Conservation (1995a:1) the Reserves Act 1977 is <nowiki>’</nowiki>more powerful than registration under the Historic Places Act 1993, or the Resource Management Act 1991 which provides for listing in a District Plan or the issuing of heritage orders.<nowiki>’</nowiki> Section 18 allows for the classifying of a reserve based on its historic merit alone. Under section 18 historic reserves include such places, objects, and natural features, and such things thereon or therein contained as are of historic, archaeological, cultural, educational, and other special interest. Section 58 lists the powers of the Minister and Administering Body in respect to historic reserves. Consistent with the earlier Reserves and Domains Act 1953, landowners are able to set up reserves on private land through application to the Minister of Conservation <nowiki>[</nowiki>s76<nowiki>]</nowiki>. A problem inherent in the Reserves Act 1977 is its focus on the <nowiki>’</nowiki>principal or primary purpose<nowiki>’</nowiki> of a reserve and the implication this creates for the management of reserves. Unfortunately, for this reason, historic values may be compromised in enhancing the primary values of a reserve such as recreation or scenery. The Department of Conservation (1995a:2) provides the example of Bowentown Heads in Tauranga Harbour, classified as a recreation reserve. The top of the pa Te Kura a Maia was damaged through the creation of a car park to cater for its primary purpose of recreation. This Act was administered by the Department of Lands and Survey until the Conservation Act 1987 was implemented at which point it was handed to the DOC who actively manage more than half of the registered reserves in New Zealand. | ||

| − | === | + | ===1980 to 1990=== |

The period 1980 to 1990 saw the consolidation of environmental law and reinforced the 1970s worldwide trend toward conservation and environmental consciousness. The changes to cultural and historic heritage legislation are the result of the culmination of ideas that began to surface in the 1980s. According to O<nowiki>’</nowiki>Regan (1990:101) the Te Maori exhibition in 1984 played an important instigative role. The effect was a heightened awareness of Maori about issues regarding possession and heritage. Questions of whose right it is to control information and manage the protection of Maori sites are currently at the forefront of the cultural and historic heritage management debate. Legislation of the late 1980s -1990s can be seen to take such matters seriously. It is a statutory requirement under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, the RMA, the HPA 1993 and Te Ture Whenua Maori Act 1993/ Maori Land Act 1993 that <nowiki>’</nowiki>Maori culture, historic, spiritual, and physical values in environmental/land-use and social planning<nowiki>’</nowiki> be considered (Harmsworth 1997:37). So far there have been varying degrees of success. This has a great deal to do with the nature of local government in New Zealand; <nowiki>’</nowiki>from the perspective of the Treaty of Waitangi it can be argued that devolution of Crown authority from central government to local authorities is inconsistent with the Crown/Maori partnership established by the Treaty and contrary to the Treaty obligation on the Crown (or central government) to protect Maori interests<nowiki>’</nowiki> (Hayward 1998:162). In the past local governments appeared reluctant to take on treaty issues. Recent legislation and the devolution of power have required local government to have a greater role in affairs of the Crown. | The period 1980 to 1990 saw the consolidation of environmental law and reinforced the 1970s worldwide trend toward conservation and environmental consciousness. The changes to cultural and historic heritage legislation are the result of the culmination of ideas that began to surface in the 1980s. According to O<nowiki>’</nowiki>Regan (1990:101) the Te Maori exhibition in 1984 played an important instigative role. The effect was a heightened awareness of Maori about issues regarding possession and heritage. Questions of whose right it is to control information and manage the protection of Maori sites are currently at the forefront of the cultural and historic heritage management debate. Legislation of the late 1980s -1990s can be seen to take such matters seriously. It is a statutory requirement under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, the RMA, the HPA 1993 and Te Ture Whenua Maori Act 1993/ Maori Land Act 1993 that <nowiki>’</nowiki>Maori culture, historic, spiritual, and physical values in environmental/land-use and social planning<nowiki>’</nowiki> be considered (Harmsworth 1997:37). So far there have been varying degrees of success. This has a great deal to do with the nature of local government in New Zealand; <nowiki>’</nowiki>from the perspective of the Treaty of Waitangi it can be argued that devolution of Crown authority from central government to local authorities is inconsistent with the Crown/Maori partnership established by the Treaty and contrary to the Treaty obligation on the Crown (or central government) to protect Maori interests<nowiki>’</nowiki> (Hayward 1998:162). In the past local governments appeared reluctant to take on treaty issues. Recent legislation and the devolution of power have required local government to have a greater role in affairs of the Crown. | ||

| Line 147: | Line 149: | ||

In terms of the evolving development of heritage management at a local level major changes to the framework of local government were established with the Local Government Amendment Act in 1989. This amendment created a three-tier arrangement by introducing the regional level into the system of national and local governance. The present system was designed to promote greater participation and accountability in planning and reduce costs for central government. | In terms of the evolving development of heritage management at a local level major changes to the framework of local government were established with the Local Government Amendment Act in 1989. This amendment created a three-tier arrangement by introducing the regional level into the system of national and local governance. The present system was designed to promote greater participation and accountability in planning and reduce costs for central government. | ||

| − | === | + | ===1990s=== |

The 1990s saw the growth of an independent historic heritage consultant industry. It is also accompanied by an increased number of independent archaeological consultants. The development of the archaeological consultant sector is perhaps most pronounced in the Auckland region. Evidence of this is illustrated in Table 2.2. | The 1990s saw the growth of an independent historic heritage consultant industry. It is also accompanied by an increased number of independent archaeological consultants. The development of the archaeological consultant sector is perhaps most pronounced in the Auckland region. Evidence of this is illustrated in Table 2.2. | ||

Revision as of 07:37, 1 May 2008

|

The content of this page has not been verified.

|

This is an ARK page.

It represents an important contribution to the Authoritive Repository of Knowledge.

A qualified professional has written this document and proper acknowledgement should be given in referencing this material. In additional the document should only be modified by the original author or approved editor with the permission of the author.

Originally written in 2002.

Contents

- 1 HISTORY OF LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENT

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 Heritage Management Prior to 1950

- 1.3 1950 To 1960

- 1.4 1960 To 1980

- 1.5 1980 to 1990

- 1.5.1 Historic Places Act 1980

- 1.5.2 National Parks Act 1980

- 1.5.3 Environment Act 1986

- 1.5.4 Conservation Act 1987

- 1.5.5 Local Government and Official Information and Meetings Act 1987

- 1.5.6 Rating Powers Act 1988

- 1.5.7 Institute of New Zealand Archaeologists (INZA)

- 1.5.8 International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS)

- 1.5.9 Local Government Amendment Act 1989

- 1.6 1990s

- 1.7 Discussion

HISTORY OF LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENT

Introduction

In order to evaluate the present system of archaeological resource management, identify problems, and suggest solutions this chapter discusses the evolution of legislation and institutions involved in historic heritage management and protection in New Zealand. For the purpose of this chapter it has been necessary to trace the development of historic and cultural heritage legislation rather than provisions for archaeological resource management per se. Legislation that can be applied to archaeological sites is more often implied or interpreted than specifically stated in statute. Provisions that specifically mention archaeological sites have been in existence since the Reserves and Domains Act 1953. However, provisions aimed at the protection of archaeological information have only been included in statute since the Historic Places Amendment Act 1975. To develop an understanding of current local authority roles in historic heritage management it has been necessary to broadly trace the principal Acts leading to the devolution of decision making resulting in the present system of local authority management of resources.

Both the prehistory and colonial history of New Zealand are relatively short in comparison with other parts of the world. It is for this reason that many people fail to value the significance of archaeological sites in New Zealand. However the significance of archaeological sites should not be underestimated. They play an important role as a physical link to the past and they are the source of archaeological information for academic inquiry. More recently archaeological sites have been recognised as a socio-cultural resource because they provide evidence of continuity, they create a sense of place and can be wahi tapu. For these reasons archaeological sites have been recognised in statute. Although archaeological information has been considered in legislation for almost a century, protection of the archaeological resource is relatively new.

At the broadest scale institutional and legislative development in New Zealand reflects change at the global level. Changes in the global economy have required New Zealand to promote itself independently and find means of income other than farming, which predominated prior to the 1970s. This has seen a diversification of the economy often physically expressed in multiform land use. In addition New Zealand and the world has witnessed the continued growth of the tourism industry. Ideologically there has been a shift from the homogenisation of the modernist era to a promotion of difference and celebration of culture characteristic of the post-modern period. New Zealanders recognised the importance of developing a national identity early on in the country’s history. In the past decade it has become evident that this identity must incorporate all of our cultures. Te Papa, the Museum of New Zealand, is testimony to this. Nationally the country has seen the progressive devolution of decision-making. At the local level communities are provided with greater roles in decisions affecting the district in which they live. They also have greater opportunities to create local identities and economies to meet the growing need to promote towns not only for tourism reasons but to create a sense of place. ’From the 1980s onwards […] heritage has become part of a community branding exercise, the creation of a point of differentiation in fostering community pride while luring visitors’ (McLean 2000b:85).

Institutional and legislative development also relate to changes in the discipline of archaeology. Development of the discipline has influenced ideas and perceptions within the institutions involved in the growing historic heritage industry. Archaeological heritage management in New Zealand has taken much longer to become established than the academic discipline. Investigation into the state of archaeological resources and the ways in which they are managed has only become the focus of attention in the past decade. This process is not unique to New Zealand. Cleere (1989:1) mentions that ’the academic discipline of archaeology and the administrative function of archaeological heritage management are twins that have developed at different rates.’ Academic archaeological inquiry in New Zealand has been a part of understanding our history from the early 1900s, first in museums and later by universities. It is only in the last twenty years however, that significant growth has occurred in the historic heritage management sector, increasingly independently of the traditional historic heritage institutions.

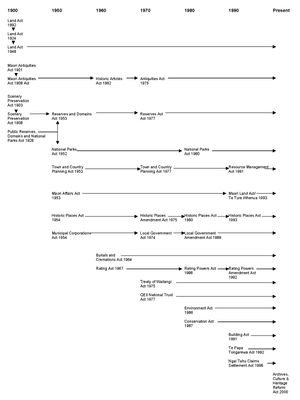

The history of legislation reflects the rapid changes this country has undergone; it reflects the attitudes of a nation trying to develop socially, culturally and economically. It is a reflection of changing global perspectives, particularly in regard to managing the environment. Figure 2.1 schematically organises the development of legislation that was, and still is in some cases, applicable to cultural and historic heritage management in New Zealand. It includes all of the Acts for which historic heritage provisions will be discussed in this and the following chapter. Figure 2.1 demonstrates how past Acts were remodelled into new pieces of legislation and indicates the Acts that are currently in use today. The figure represents the reorganisation rather basically as many provisions of early Acts were repealed or split among several new statutes. The aim is to illustrate the progression of the legislative change that has a relationship to historic and/or cultural heritage management.

Heritage Management Prior to 1950

The first institutions with a responsibility for managing and promoting natural, cultural and historic heritage were museums. The Auckland Museum was first established in 1852, and Wellington’s Colonial Museum, Otago and Canterbury Museums followed in 1865, 1868 and 1870 respectively. In addition to Dunedin’s Otago Museum, the Otago Early Settlers Museum was established in 1898 to explore early colonial history. In 1919 the Otago Museum employed H.D. Skinner who began teaching a one-year archaeology course in 1920. During his time at Otago Museum, Skinner arranged the 1932 appointment of David Teviotdale who became the first professional archaeologist employed in New Zealand (Trigger 1989:140). Other museums employed archaeologists much later, with Auckland and Canterbury doing so in the 1960s.

Early legislation in New Zealand was passed in a piecemeal fashion and resulted in numerous Parliamentary Acts related to specific locations and issues, rather than for application to the nation. Many of the early statutes have been consolidated over time forming bodies of legislation that apply to New Zealand as a whole. Most notably the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) incorporated over seventy of the previous statutes. Legislation aimed at protecting New Zealand’s historic and cultural heritage has been in existence for almost a century. Natural heritage preservation can be traced back still further to the Public Reserves Act 1854. Prior to the 1950s several statutes could be applied to historic heritage protection.

Land Act 1892

Perhaps the first Act of New Zealand’s Parliament to be applied to the protection of heritage was the Land Act 1892 that enabled limited purchases such as that of Ships Cove in the Marlborough Sounds in 1896 (McLean 2000b:75). Amendments to the Land Act were consolidated with the Land Act 1924. Under Part XI of this Act the Governor General could set aside Crown land for a reserve. Theoretically this Act could be applied today, as it is still in use as the Land Act 1948. Under section 167 the Minister (currently the Minister of Conservation) may set apart as a reserve any Crown land for any purpose which is desirable in the public interest. Although this is so, the historic heritage provisions of the Land Act 1948 have been surpassed by a number of other Acts which are written more specifically for the purpose of historic heritage management. The Reserves and Domains Act 1953 followed by the Reserves Act 1977 are examples.

Maori Antiquities Act 1901

During the initial period of colonial New Zealand there was early recognition of the importance of preserving artefacts as well as sites. This stemmed from an awareness of the value cultural items had gained through their trade. Between 1769 and 1901 the collection and trade of Maori artefacts proliferated, ’it was not until 1898 that the conscience of any Colonial politician was sufficiently stirred for the matter of the protection of cultural and scientific specimens to be raised in the House of Representatives’ (McKinlay 1973:13). In 1901 the Maori Antiquities Act was passed with the aim of preventing the removal of antiquities from New Zealand. This Act empowered the Government to purchase items deemed important for the history of the colony. The Act, however, did not prevent continued trade and export and, as a result, penalties for the export of Maori artefacts were deemed necessary and were introduced in 1904. The Maori Antiquities Act was consolidated in 1908 and remained the legislation that controlled the export of Maori artefacts from the country until the Historic Articles Act was passed in 1962 (McKinlay 1973:18).

Scenery Preservation Act 1903

According to Leach (1991:83) measures designed to protect cultural heritage were initiated at the turn of the century with the Scenery Preservation Act 1903. This Act also signified a conscious beginning of the development of a New Zealand identity. Under the Scenery Preservation Act 1903 a Commission of five people was set up in order to acquire blocks of land of scenic, historic or thermal significance. In terms of archaeology it is significant that the Commission included three individuals with a keen interest in Maori prehistoric sites (Leach 1991:87). The Commission, although achieving a great deal in its short existence, was revoked following the Scenery Preservation Amendment Act 1906. Administration was passed to the Ministry of Lands and Survey whose approach was to be more cost effective. The 1906 Amendment Act made it an offence to damage the historic features of a reserve. In 1910 the Scenery Preservation Act was amended again, giving the ’government power to take native land for scenery preservation purposes’ (Leach 1991:86). Acquisition of land reached a peak in 1911-1912 but little attention was given to archaeological sites. During 1917 W. H. Skinner [Commissioner of Crown Lands for Canterbury] and J. Thomson [Director of the Dominion Museum] tried to rectify this due to their concerns for the preservation of Maori rock art in Canterbury, the issue was not raised again until the setting up of the National Historic Places Trust in 1954 (Leach 1991:87).

Public Reserves Act 1908

The Public Reserves Act 1908 is similar to both the Land Acts and the Scenery Preservation Acts in that it contains provisions for setting aside land for reserve purposes. These three Acts are a few of many Acts of New Zealand Parliament that contain provision for reserves. Other examples include the Education Reserves Act 1928 and the Defence Act 1908. The Public Reserves, Land, and Scenery Preservation Acts, however, are the most likely of the Acts to have been applied to historic and cultural heritage. Under the Public Reserves Act 1908 power was given to both the Governor General and local authorities to create reserves. In 1928 provision for creating national parks was added to the Act and it was renamed the Public Reserves, Domains and National Parks Act 1928. Under section 71 the Governor General could, among other things, make land subject to the Scenery Preservation Act 1908 into a national park. The national park section of the Public Reserves, Domains and National Parks Act 1928 was moved into the National Parks Act 1952. However the new National Parks Act was concerned solely with scenery and natural features. The following year the provisions for Reserves and Domains were incorporated into the Reserves and Domains Act 1953.

During this early period, legislation concerning historic heritage was written not only to reflect the ideals of the institutions concerned with its protection, but also to protect the rights of private land owners. In many ways those ideals have persisted in legislation today. According to Vossler (2000:58)

’Any legislation which has at its core an objective to protect places of identified heritage value is, on balance, likely to impinge on the rights of private owners. Given the general reluctance of many governments to introduce legislation which interferes with such rights a precautionary approach is often applied by legislators.’

Although interest was developing during the provincial centennials of the 1930s it was the 1940 national centennial celebrations of European colonisation that led to an increased interest in items of historical importance to the nation. According to Lucas (1984:5) the purchasing of Busby Estate at Waitangi and its presentation to the nation in 1940 by Lord and Lady Bledisloe signified the first step towards a New Zealand Historic Places Trust. In 1943 the Government purchased Pompallier House and the management and control became the duty of the Department of Internal Affairs. With this purchase came a realisation of the need for ’a systematic way of dealing with our historic buildings instead of the one off approach that had applied up until that time’ (Lucas 1984:5). However, it took another ten years and the Private Members Bill introduced by Duncan Rae in 1952 to prompt the Government to take action (Lucas 1984:5).

1950 To 1960

According to Davidson (1974:6) the late 1950s saw a rapid development in New Zealand archaeology. Anthropology departments were established at both Auckland and Otago universities in the 1950s. Auckland University employed its first archaeologist Jack Golson in 1954. In 1958 Peter Gathercole took up a joint position at the Otago Museum, lecturing stage one anthropology/archaeology at the University of Otago (Gathercole 2000:208).

In 1951 the New Zealand Site Recording Scheme was developed through a grant received by the Hawke’s Bay Branch of the Royal Society of New Zealand to investigate the setting up of such a scheme (Davidson 1974:2). The Constitution for the New Zealand Archaeological Association (NZAA) was drafted in 1955 (Golson 1955:349) and the Association was up and running by 1958. Simultaneously the Site Recording Scheme was instituted. Under the scheme there were to be district file keepers who collected, processed and assigned site numbers and a central file for the country. The scheme was to ’provide a national framework for the recording of prehistoric sites in a simple but systematic way.’ (Daniels 1971:77). The primary purpose of the scheme was to provide a research tool rather than a protection measure; however, over time its role in the protection of sites has become increasingly important. This rapid development in archaeological institutions is also reflected in the legislation developed during the period 1950 to 1960.

Historic Places Act 1954

The other significant historic heritage institution to be set up in the 1950s was the National (now New Zealand) Historic Places Trust set up by the Historic Places Act 1954. The purpose of the organisation, outlined in section 3 of the 1954 Act, was

’preserving and marking and keeping permanent records of such places and objects and things as are of national or local historic interest or of archaeological, scientific, educational, architectural, literary, or other special national or local interest.’

Under this Act penalties could be imposed on anyone who interfered with a historic place. At this time the National Historic Places Trust was administered by the Department of Internal Affairs; this continued until 1987 when the Trust came under the jurisdiction of the DOC. The Historic Places Act did not, at this stage, contain any specific provisions for archaeological resource management, these were introduced with the Historic Places Amendment Act 1975. In the beginning the Trust relied heavily upon voluntary work. Initially employing one paid staff member, the number of staff had only increased to thirteen by 1975 (McLean 2000a:35).

Town and Country Planning Act 1953

During the 1950s a number of statutes were introduced which relate to the management and protection of historic and cultural heritage. The Town and Country Planning Act 1953 provided the legal framework for the preparation of the planning schemes by local bodies (McKinlay 1973:49). The Town and Country Planning Regulations 1960 provided the ’means for the preservation of objects and places of historical or scientific interest or natural beauty.’ (Daniels 1970:51). This was achieved by giving authority to local bodies to keep a register of places or objects of interest or beauty. These regulations prescribed the detailed procedures to be followed in preparing schemes. Regulations required that every scheme included inter alia, "a scheme statement", which has a statement that described the particular purposes of the district scheme. The third schedule of the regulations provided a suggested form of scheme statement. Of interest is Clause 2 Part X of the suggested scheme statement stating:

’The objects and places of historical or scientific interest or natural beauty listed in Appendix VIII hereto are to be registered, preserved and maintained so far as the powers of the Council or local authority from time to time permit.’

Local bodies were also required to notify landowners and occupiers of an item’s location, in the hope of protecting sites on private land. In addition it specified that no person shall wilfully destroy, remove or damage an item listed in the register. This system of management was advantageous because it created responsibility and awareness at a local level. Unfortunately there was a lack of national co-ordination and guidance. According to Neave (1981:5), the Town and Country Planning Acts never made it compulsory for district schemes to introduce provisions for heritage protection. Kelly (2000:122) mentions that ’[the] level of protection afforded by these district plans was entirely at the whim of the local authority in question.’

This Act also allowed for the cancellation of register entries although to cancel a registration would require public notification. Brown (1962:74) expressed concern over the effect cancellation of entries had on the protection of sites, a major problem being the difficulty of monitoring the activities of twenty four Local Bodies which, under the Act, could include and take sites off a register at will. The Town and Country Planning Act 1953 and amendments were consolidated by the Town and Country Planning Act 1977. It is interesting to note that by 1977 matters to be dealt with in Regional and District Schemes include marae, urupa reserves, pa, and other traditional and cultural Maori uses. In 1991 the Act was repealed by the RMA.

Municipal Corporations Act 1954

In terms of the effect land subdivision may have on historic heritage, theoretically section 351 of the Municipal Corporations Act 1954 could be applied to protect a historic heritage item under threat from development. The Act was repealed by the Local Government Act 1974. Today subdivision of land comes under the RMA 1991 and remains within the jurisdiction of territorial authorities.

Reserves and Domains Act 1953

The Reserves and Domains Act 1953 stemmed from the Public Reserves, Domains and National Parks Act 1928 and repealed the Scenery Preservation Act 1908. The Reserves and Domains Act 1953 included various provisions for historic heritage and, according to the Department of Conservation (1995a:2), ’this legislation, for the first time, made it clear that historic reserves were a separate category from scenic, thermal, and other reserves.’ Part V of the Reserves and Domains Act 1953 made provision for establishing historic reserves. Private historic reserves could be set up with agreements between private landowners and the Minister [s65]. This is a similar provision to the heritage covenant of the Historic Places Act, although to become a reserve the Minister must be satisfied that its creation is for the public good. However, the ability of the Minister of Lands to revoke a reservation [s18] was a source of concern (McFadgen 1966:94). The Act also allowed the Minister to promote, supervise or authorise excavations by scientific organisations provided they had the consent of the landowner [s67]. Interestingly section 67 also contained the provision that nothing in the section ’shall be deemed to prevent the owner of any land from making any such excavation or carry on any such activities on his land’. The Reserves and Domains Act 1953 was subsequently repealed by the Reserves Act 1977. Currently the Minister may still require survey, including excavation, but since 1975 nothing in the Reserves and Domains Act is to contravene Historic Places Act.

Maori Affairs Act 1953

Theoretically the Maori Affairs Act 1953 could be applied to the protection of archaeological sites. Under Section 493 of this Act ’the Governor General, on the recommendation of the Maori Land Court could set aside as a reserve any Maori Land which is, among other things, of scenic or historic interest.’ (McFadgen 1966:94). Brown (1962:77) was of the opinion that this ’does apply very well, but only to Maori owned land.’ Te Ture Whenua/The Maori Land Act 1993 repealed the Maori Affairs Act 1953.

1960 To 1980

In 1960 "threatened" and "scheduled" categories were added to the NZAA Site Recording Scheme forms: threatened for obvious reasons; scheduled being for sites of great importance to New Zealand history. These categories were important additions for the fact that information gathering could become more focused depending on whether or not a site was at risk of disappearance. The focus of archaeology in the 1960s was on information recovery, rather than the preservation of archaeological information or sites for future generations. In 1961 the idea of an artefact-recording scheme was developed (Daniels 1963:146), but the scheme was never implemented. In 1966-1967 historic sites were introduced into the site recording scheme (Davidson 1974:13), although their inclusion was subject to much debate. In 1969 a permanent archaeologist was appointed to the staff of the NZHPT (Davidson 1974:13).

The twenty-year period 1960 to 1980 was significant in the development of heritage related legislation primarily because of increased worldwide environmental awareness.

’The development pressures of the 1960s and the environmental movement of the 1970s had a profound effect on archaeological heritage management. It is significant that almost every European country enacted new antiquities legislation during the 1970s’ (Cleere 1989:4).

The rapid development of legislation containing historic heritage provisions characteristic of the 1950s did not continue into the 1960s. It can be inferred that the earlier period legislation was allowed time to settle in order to witness its development and interpretation. McFadgen and Daniels (1970:160) believe it was due to apparent inadequacies in legislation relating to archaeological sites that the NZAA began to try and change legislation from the 1960s on. The period 1960-1980 is characterised by various amendments to historic heritage provisions as the legislation was tried and tested. The period is also characterised by an apparent shift in attitude toward a greater emphasis on conservation.

Historic Articles Act 1962

The Historic Articles Act 1962 surpassed the Maori Antiquities Act 1908 and differed for the fact that it aimed to control rather than prevent the export of historic articles and items of scientific importance, due to its concern for the rights of individual owners. McKinlay (1973:42) criticised the Act for placing importance on the artefact rather than its archaeological or scientific significance and for making no provision preventing the destruction of archaeological sites by fossickers of historical items. The Act was too narrow in its focus. It was repealed by the Antiquities Act 1975.

Burials and Cremations Act 1964

The Burials and Cremations Act implemented in 1964 can still be applied to the protection of historic graveyards. Decisions as to whether historic cemeteries survive reside with the Minister of Health, who may give the authority to remove gravestones and monuments under section 45 and bodies under section 51. In 1979 subsection 2(A) was added to section 45, which requires the NZHPT to be notified of any proposal to remove historic gravestones and monuments. The Act does not apply to Maori burial grounds [s3].

The 1970s saw a ’world-wide swing towards conservation legislation’ (Fung and Allen 1984:216). This was accompanied by an increasing sense of the need for a national and indigenous identity for New Zealand. It is evident that the cultural and natural landscapes were considered intricately linked, natural and cultural/historic heritage being encompassed together under the body of legislation that came from this time period. This linkage has had a significant impact on the way archaeological sites and cultural heritage are perceived; ’sites relevant to a developing national ethos are now being managed like any other resource.’ (Fung and Allen 1984:217). Of significance for historic heritage preservation and management is the devolution of responsibility for decision making to the local level. This is a theme that is increasingly propagated under the present system, and the proposal to give greater responsibility for heritage to Local Government under the Proposed Resource Management Amendment Bill 1999.

Local Government Act 1974

The Local Government Act 1974 was written in order to devolve power from Central Government by setting in place the appropriate framework for decision making and governance at a local level. It was an extension of the principals of the Town and Country Planning Act. However, it was not until the late 1980s that major changes to the Local Government Act created greater accountability in decision making at the local level. This was achieved through the introduction of a three-tier government structure introduced in the Local Government Amendment Act 1989. The PCE report (1996a:80) mentions that through legislative responsibilities under this Act, such as the promotion of economic well-being or the promotion of regional tourism, local authorities could ’carry out significant heritage-related work.’

Historic Places Amendment Act 1975

According to Barber (2000:23) ’archaeological site protection was first recognised in legislation under the Historic Places Amendment Act 1975’. This Act includes a definition of an archaeological site; which included a rolling date inclusive of items over one hundred years old. The Amendment Act also introduced sections 9F to 9N. These sections refer specifically to archaeological sites. Section 9F(1) made it unlawful to destroy, damage or modify the whole or part of a site whether registered under section 9G or not. Section 9F(2) gave the NZHPT the authority to grant permission to destroy, damage or modify a site and section 9F(3) made the cost of scientific investigation the responsibility of those intending to destroy, damage or modify a site unless they were destroying, damaging or modifying for the purpose of farming. Section 9G required the NZHPT to develop and maintain a Register of archaeological sites. In response to section 9G the NZAA Site Recording Scheme Central File was passed to the NZHPT in order that the NZHPT could fulfil their statutory obligations under the Historic Places Amendment Act 1975 (Smith 1994:289). The NZAA Site File’s newly created dual function was as a scientific tool and a planning mechanism (problems related to this are discussed in Chapter Three). The NZHPT then developed the New Zealand Register of Archaeological Sites (NZRAS), a selection of archaeological sites that includes a small number of the archaeological sites recorded in the NZAA Site File. Section 9H required authorisation from the NZHPT for any archaeological investigation, and sections 9H and 9K dealt with providing information on registered archaeological sites for the District Land Register and district schemes. Sections 9L and 9N detailed the rights of appeal and offences.

In the mid 1970s a joint project between the NZHPT and the NZAA set up CINZAS (Central Index of New Zealand Archaeological Sites) a computerised database of the NZAA paper file that became operational in 1982 (Tony Walton pers.com 13/9/01). The original objective was to include all Site Record Form information, including site descriptions, aids to relocation and additional free text. However the setting up of the database coincided with a rapid growth in the number of records in the file in the late 1970s and 1980s. Due to resource constraints the amount of information on each archaeological site had to be scaled down, the inclusion of free text information was considered beyond resource capabilities (Tony Walton pers.com 13/9/01). The database continues to operate using a custom written program. It includes core data on archaeological sites, site type, grid reference and whether a site is Maori or European for example.

Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975

Up until the 1970s Maori issues were not considered in statutes related to planning and land use (Matunga 1997:109). The Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 has meant that indigenous rights must be adhered to. It has important consequences for resource management and historic heritage protection due to the fact that the purpose of this Act was to establish a Tribunal to make recommendations and claims regarding the practical application of the principals of the Treaty of Waitangi.

’Full Maori participation in decision-making regarding the conservation and protection of historic places, archaeological sites and wahi tapu is guaranteed through the Treaty of Waitangi, and through the Acts of the New Zealand Parliament and International Conventions, Statutes and Accords’ (Allen 1998:17).

The Queen Elizabeth the Second National Trust Act 1977

The Queen Elizabeth the Second National Trust Act 1977 can be associated with heritage protection; under section 20(2)(d) one of the Trust’s functions is to undertake the identification and classification of potential reserves and recreation areas considered to be of national, regional, local or special significance. The purpose of this Act is to protect open space and landscape features; it is a mechanism by which private landowners may manage heritage items on their land in perpetuity. According to Allen (1998:13) however, ’[t]he QEII Trust deals mainly with the natural environment leaving heritage matters to the Historic Places Trust.’ The administration of the Act currently resides with the DOC.

The Antiquities Act 1975

Two of the statutes from the period under review in the above paragraphs directly apply to heritage protection and management in this country today. The first is the Antiquities Act 1975, which controls the trade and export of Maori artefacts. Under the Act all artefacts are the property of the Crown. However this is inconsistent with the Treaty of Waitangi and according to the PCE Report (1996a:A28) the Act has ’proved inadequate to prevent such export and to obtain repatriation of artefacts.’ In order to rectify the situation the Taonga Maori Protection Bill was introduced. The Bill is currently on hold pending results of the Taonga Maori Review. The Antiquities Act was administered by the Department of Internal Affairs up until 2000 when it came under the jurisdiction of the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Artefacts found in the course of archaeological investigation are subject to the Antiquities Act 1975. Section 11(5) makes it an offence if one fails to notify the chief executive of the nearest public museum on the discovery of an artefact.

Reserves Act 1977

The second Act of the 1970s still applicable to historic heritage management today is the Reserves Act 1977. This Act makes provision for the acquisition, control, management, maintenance, development and use of reserves. According to the Department of Conservation (1995a:1) the Reserves Act 1977 is ’more powerful than registration under the Historic Places Act 1993, or the Resource Management Act 1991 which provides for listing in a District Plan or the issuing of heritage orders.’ Section 18 allows for the classifying of a reserve based on its historic merit alone. Under section 18 historic reserves include such places, objects, and natural features, and such things thereon or therein contained as are of historic, archaeological, cultural, educational, and other special interest. Section 58 lists the powers of the Minister and Administering Body in respect to historic reserves. Consistent with the earlier Reserves and Domains Act 1953, landowners are able to set up reserves on private land through application to the Minister of Conservation [s76]. A problem inherent in the Reserves Act 1977 is its focus on the ’principal or primary purpose’ of a reserve and the implication this creates for the management of reserves. Unfortunately, for this reason, historic values may be compromised in enhancing the primary values of a reserve such as recreation or scenery. The Department of Conservation (1995a:2) provides the example of Bowentown Heads in Tauranga Harbour, classified as a recreation reserve. The top of the pa Te Kura a Maia was damaged through the creation of a car park to cater for its primary purpose of recreation. This Act was administered by the Department of Lands and Survey until the Conservation Act 1987 was implemented at which point it was handed to the DOC who actively manage more than half of the registered reserves in New Zealand.

1980 to 1990

The period 1980 to 1990 saw the consolidation of environmental law and reinforced the 1970s worldwide trend toward conservation and environmental consciousness. The changes to cultural and historic heritage legislation are the result of the culmination of ideas that began to surface in the 1980s. According to O’Regan (1990:101) the Te Maori exhibition in 1984 played an important instigative role. The effect was a heightened awareness of Maori about issues regarding possession and heritage. Questions of whose right it is to control information and manage the protection of Maori sites are currently at the forefront of the cultural and historic heritage management debate. Legislation of the late 1980s -1990s can be seen to take such matters seriously. It is a statutory requirement under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, the RMA, the HPA 1993 and Te Ture Whenua Maori Act 1993/ Maori Land Act 1993 that ’Maori culture, historic, spiritual, and physical values in environmental/land-use and social planning’ be considered (Harmsworth 1997:37). So far there have been varying degrees of success. This has a great deal to do with the nature of local government in New Zealand; ’from the perspective of the Treaty of Waitangi it can be argued that devolution of Crown authority from central government to local authorities is inconsistent with the Crown/Maori partnership established by the Treaty and contrary to the Treaty obligation on the Crown (or central government) to protect Maori interests’ (Hayward 1998:162). In the past local governments appeared reluctant to take on treaty issues. Recent legislation and the devolution of power have required local government to have a greater role in affairs of the Crown.

Historic Places Act 1980

In terms of the NZHPT’s role, amendments to the previous Historic Places Act were consolidated in the Historic Places Act 1980. The legal powers given to the NZHPT under the 1975 Amendment Act were augmented in the 1980 Act. Sections 35 to 42 dealt with heritage buildings, and section 35 established the buildings classification system. The classifications system did not provide specific protection. This was achieved through the introduction of the protection notice under section 36 of the 1980 Act. To implement classification the NZHPT set up a register of historic buildings, similar to the archaeological register required under the 1975 Amendment Act except that buildings were classified from A to D relative to their significance. Once a protection notice was issued by the Trust any building subject to the notice was protected from demolition or alteration. According to Comrie (1988:8), ’they are the only way in which a classification by the Trust can have any legal or binding effect’. Section 36(2) made provision for the inclusion of buildings subject to a protection notice in district schemes. A further two heritage categories were introduced in the 1980 Act; historic areas in section 49 and traditional sites in section 50. The Minister of Maori Affairs was required to receive any application for a place to be declared a traditional site. The introduction of the traditional site category signifies an important step in the recognition of Maori values and heritage issues as it separates Maori values from archaeological or other historic heritage values.

Heritage Covenants were introduced under section 52. Covenants allow the NZHPT to enter into an agreement with landowners who wish the historical significance of their property to be protected in perpetuity. Heritage Covenants also mean that the future of an historic place can be recorded and enforced and any financial assistance provided by the NZHPT be safeguarded (Burns 1984:34). In terms of archaeological sites, the section 9 provisions of the 1975 Amendment Act were carried over to the 1980 Act, and were contained within sections 43 to 48. Offences against the Act were moved to Part IV. During the 1970s and 1980s the NZHPT placed an emphasis on archaeological site survey and recording, increasing the NZAA file from less than 10,000 recorded sites to more than 40,000 between 1975 and 1980 (McLean 2000a:39).

National Parks Act 1980

The National Parks Act 1980, previously administered by the Department of Lands and Survey is currently overseen by the DOC. Formerly the National Parks Act 1952 the 1980 Act added sites of archaeological or historic importance to the preservation of scenic and natural features. This is an interesting addition as initially this Act was combined with the Reserves, Domains and National Parks Act 1928 and included provision for historic heritage. Once separated in 1952 the National Parks Act no longer included such provisions. The 1980 Act has a purpose to preserve natural and cultural heritage. This is detailed in section 4 ’[…] preserving in perpetuity as national parks, for their worth and for the benefit, use and enjoyment of the public […] (2)(c) sites and objects of archaeological and historical importance’. Section 9 applies to the acquisition of land for national parks and section 12 to specially protected areas in national parks. Both provisions can be used for the preservation of archaeological sites.

Environment Act 1986

The Environment Act 1986 established the Ministry for the Environment (MfE). The functions of the ministry include policy advice to the government and environmental administration, implementation of sustainable management, administration of statutes, advocacy, education and advice to others. The Act also set up the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE) whose role is that of an independent watchdog. This is achieved by reviewing agencies involved in environmental management, and by investigating the effectiveness of environmental planning. ’Both the Ministry and the Commissioner have a firm basis in statute and, unlike the previous situation are not mere window-dressing capable of being abolished at the whim of the Government.’ (Wilde 1987:9). Of significance to historic heritage management the PCE commissioned an inquiry into the state of historic and cultural heritage management in New Zealand in 1994/1995 (PCE 1996a, 1996b). This in turn led to the Heritage Management Review of 1998 (DOC 1998a, 1998b, 1998c, 1999).

Conservation Act 1987

Under The Conservation Act 1987 the Department of Conservation (DOC) was set up with the duty to preserve natural and cultural features of New Zealand. The conservation estate covers almost a third of New Zealand’s land area which was previously administered by the Department of Lands and Survey and the Forest Service (Wilde 1987:10). The Department procured CINZAS, and currently manages the NZAA Site Recording Scheme Central File. In 1988 the archaeologists employed by the NZHPT were transferred to the DOC but continued to service the NZHPT’s statutory archaeological requirements through formal agreement until 1993, at which point the DOC withdrew its archaeological services (Barber 2000:25). According to the PCE (1996b:A26) this decision was based on legal advice to the effect that it was no longer appropriate for archaeological services to be provided to the NZHPT as it was not a Crown entity. In 1995 the DOC published its ’Historic Heritage Strategy’ defining the Department’s priorities in regard to historic heritage. The strategy made it a priority for the DOC to manage historic heritage on the conservation estate. The NZHPT is considered the leading advocate for "off-estate" historic heritage although the DOC provides a supportive role.

’At first glance the outcome of the changes in legislation and administrative organisation for the protection of archaeological sites looks messy’ (Allen 1988:151-152). The advantage of this system of management is regional representation; the Department employs more archaeologists than any other institution in New Zealand. Even so, Allen (1991:17) points out that ’although the Conservation Act 1987 directs the Department to preserve and protect both natural and historic resources, the Department sees its primary function as nature conservation.’ In regard to Maori, section 4 makes it a policy of the Department that tangata whenua should participate in the management of sites of significance to them.

It was through the Conservation Act 1987 that central government had a direct link to historic heritage management. Schedule 1 required the DOC to administer the Historic Places Act; previously the NZHPT had liaised with the Ministry of Internal Affairs. ’Although the overall responsibility for administering the HPA 1993 currently rests with the Department of Conservation, the agency which largely gives effect to the purpose and principals of the Act is the New Zealand Historic Places Trust’ (Vossler 2000:62). The PCE (1996a) inquiry into historic and cultural heritage management revealed that the DOC was not managing historic and cultural heritage appropriately, particularly following the heritage strategy of 1995 which shifted the Department’s focus to the conservation estate. ’Even on conservation estate, intense internal competition for funding is hampering DOC’s progress with integrated heritage management.’ (PCE 1996:34). On October 1st 2000 the HPA 1993 was repealed from Schedule 1 of the Conservation Act 1987 by s12 of the Archives, Culture, and Heritage Reform Act 2000. Since then the administration role played by the DOC has been transferred to the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, formally known as the Ministry of Cultural Affairs.

Local Government and Official Information and Meetings Act 1987

Under this Act any person may apply to a territorial authority for a land information memorandum (LIM) for any land in a district of that authority. Section 44A(2)(d) requires LIMs to include information concerning any consent, certificate, notice, order, or requisition affecting the land or any building on it previously issued by the territorial authority. Section 44A(2)(g) requires LIMs to include information notified to a territorial authority by any statutory organisation having the power to classify land or buildings such as the NZHPT under the HPA 1993.

Rating Powers Act 1988

The Rating Powers Act 1988 repealed the Rating Act 1967 which Neave (1981) lists as one of the Acts inhibiting the provision of financial assistance by local authorities for historic heritage. In 1992 the Rating Powers Amendment Act introduced Part XIIB. Sections 180G and 180H provide local authorities with the ability to adopt policies for the remission or postponement of rates for the purpose of preserving voluntarily protected historic heritage within the district.

Institute of New Zealand Archaeologists (INZA)

The Institute of New Zealand Archaeologists was set up in 1984 when some professional members of the NZAA saw the need for oversight in archaeological consultant and assessment work and the standardisation of rates of pay (Coster 1984). The institute developed its own code of ethics and professional membership requirements. John Coster (pers.com. 3/8/2001), former chair of INZA, believes the institute met its demise in 1997 for a variety of reasons including low membership numbers and lack of support from many contract archaeologists and established institutions, for example museums, universities and the NZHPT.

International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS)

Established in 1965, this international organisation has committees in more than 107 countries. ICOMOS is the principal advisor on conservation and preservation of monuments and sites to UNESCO. The New Zealand National Committee of ICOMOS was founded in 1987. ’The international codes of practice established by ICOMOS and its other affiliated member countries offered benchmarks which could be emulated in New Zealand’ (Kelly 2000:123). In 1993 ICOMOS New Zealand published the ICOMOS New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value. This document has had considerable impact considering the size of the organisation in New Zealand. It has become the standard for conservation practice in institutions such as the DOC and the NZHPT. According to Mary O’Keeffe (pers.com 30/7/2001), chair of ICOMOS New Zealand, most councils have taken up the principals of the charter in some form or another, some councils (Christchurch City Council) have made the ICOMOS New Zealand Charter a Council policy for dealing with historic and cultural heritage.

Local Government Amendment Act 1989

In terms of the evolving development of heritage management at a local level major changes to the framework of local government were established with the Local Government Amendment Act in 1989. This amendment created a three-tier arrangement by introducing the regional level into the system of national and local governance. The present system was designed to promote greater participation and accountability in planning and reduce costs for central government.

1990s

The 1990s saw the growth of an independent historic heritage consultant industry. It is also accompanied by an increased number of independent archaeological consultants. The development of the archaeological consultant sector is perhaps most pronounced in the Auckland region. Evidence of this is illustrated in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2 demonstrates that in the decade since the introduction of the RMA the amount of archaeological work being completed by consultant archaeologists has increased substantially. In the years prior to 1991 the majority of archaeological survey and assessment reports were produced by the NZHPT and the New Zealand Forest Service.

Table 2.2: Number of archaeological survey and assessment reports produced in the Auckland region between 1900 and 2000

| Year | Total number of reports | Number of reports produced by consultants | Percent of reports produced by consultants |

| 1900-1950 | 4 | 0 | 0% |

| 1951-1960 | 8 | 0 | 0% |

| 1961-1970 | 32 | 0 | 0% |

| 1971-1980 | 118 | 10 | 8% |

| 1981-1990 | 154 | 17 | 11% |

| 1991-2000 | 388 | 313 | 81% |

(Source of information: Auckland Regional Council’s Cultural Heritage Inventory)

Of the seven Acts created in the 1990s two of these dominate the management and protection of historic heritage. They are the RMA and the HPA 1993, both of which are discussed in Chapter Three as the primary tools of historic heritage management in New Zealand. Other Acts related to historic and cultural heritage which often work in conjunction with the two primary Acts are discussed below.

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Act 1992

In addition to the RMA 1991 and HPA 1993 a number of Acts emphasise the growing awareness of cultural heritage values to emerge during the 1990s. The aim of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Act 1992 was to create a museum to ’present, explore, and preserve both the heritage of its cultures and knowledge of the natural environment’ [s 4]. The museum was created in recognition of the need to promote and develop a uniquely New Zealand identity. Such ideas are not new and were evident at the turn of the century, for example the creation of the Polynesian Society in 1892, the early colonial legislation for the preservation of heritage, and the centennial celebrations. The creation of the museum plays an important role in heritage management as an educational tool and for the promotion of New Zealand’s culture and historic heritage.

Te Ture Whenua Maori Act 1993/Maori Land Act 1993

Te Ture Whenua Maori Act 1993/ Maori Land Act 1993 replaced the Maori Affairs Act 1953. Similarly it has the potential to protect archaeological sites. The Act is administered by Te Puni Kokiri. Its purpose is to promote the identification, protection, preservation, and conservation of the historical and cultural heritage of New Zealand. This can be achieved through the creation of reserves. If the land is not Maori or Crown owned land the Maori Land Court can recommend that the Crown purchase land for a reserve.

The Building Act 1991

The purpose of the Building Act 1991 is to ensure that buildings are safe and sanitary. In conjunction with the Building Code the Building Act 1991 controls the design of buildings. According to the PCE (1996a:48) earthquake insurance provisions and the lack of heritage value recognition in the building code has potential to create the greatest effect on heritage buildings due to the cost of insurance and structural upgrading required for such buildings. The Building Act contains some provision for historic buildings. Section 27(2)(c) requires that territorial authority keep records of any statutory authority, such as the NZHPT, which has the power to classify land or buildings for any purpose. Section 31(2)(b) requires that PIMs (Project Information Memoranda) include NZHPT notified sites.

The Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998

Under the Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998 section 210(2) creates a mandate for the NZHPT or the Environment Court to determine if Te Rununga o Ngai Tahu is an affected party in relation to an archaeological site within their statutory area. It is appropriate to note that due, in part, to the result of Ngai Tahu settlement claims the historic and cultural heritage management inquiry was initiated by the PCE in 1995/1996.

Archives, Culture and Heritage Reform Act 2000

The most recent Parliamentary Act applicable to historic and cultural heritage management is the Archives, Culture and Heritage Reform Act 2000. This transformed the Ministry of Cultural Affairs into the Ministry for Culture and Heritage which now administers, among others, the Antiquities Act 1975, the Historic Places Act 1993 and Te Papa Tongarewa Act 1992. The most obvious shift in term of archaeological heritage management is the removal of the HPA 1993 from the supervision of the DOC to administration by the new Ministry. In this way a new distinction is drawn between natural/environmental heritage and cultural heritage. It is interesting that after a century of combining the natural environment with human history that the two concepts are separated with the introduction of the new Ministry.

Discussion

This chapter has demonstrated that over the past one hundred years a significant amount of effort has been invested in deciding how to define and protect New Zealand’s historic heritage. The result being that there is a substantial amount of legislation for the management and protection of historic heritage, and a variety of organisations with statutory provision for historic heritage management (NZHPT, MfE, DOC, Ministry for Culture and Heritage, regional and territorial authorities). The development of the historic heritage management industry has been influenced by a number of factors including changing global ideas. In the last two decades increased environmental awareness has led to the development of sustainable management strategies. In addition there has been global recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights, evident in the development of international conventions and charters for example; the ICOMOS charter and the International Code of Ethics approved by the World Archaeological Congress in 1991. Nationally, the driving force behind heightened cultural heritage awareness is that an indigenous identity for the country is considered imperative. Significant progress has been made at a national level due to the motivation of practitioners in institutions such as the NZAA, NZHPT, universities and museums, also independent practitioners and tangata whenua who have influenced both the development of the legislation and historic heritage management practice in this country. The PCE report (1996a:47) on historic and cultural heritage management found that ’in many communities key individuals both inside and outside agencies have driven attempts to recognise and protect historic and cultural heritage’. The result is reflected locally in different historical landscapes created through the retention of places of historical significance whether they be a historic building or streetscape, a pa site or a shipwreck.

In the last twenty to thirty years New Zealand has developed an enhanced sensitivity toward the importance of valuing Maori cultural heritage and the ownership of information, including archaeological information. A consequence of such trends has been a progression toward protecting archaeological sites for future generations rather than just the information contained within them. Today it is recognised that historic heritage cannot be representative if comprised solely of old, aesthetically pleasing buildings. To collate a historically correct sample, a wide range of heritage items must be preserved, including archaeological sites. In legislation archaeological sites are valued primarily for their information content. Today archaeological sites are recognised to have a number of values, for example they are valued for their significance to Maori, they have value as educational tools and as physical reminders of the past. This has meant that a range of management options need to be explored before archaeological sites are destroyed through excavation.

Cultural and natural heritage have primarily been linked in New Zealand legislation, particularly in early statutes such as the Scenery Preservation Acts and the Public Reserves and Domains Acts. Historic heritage, in its own right, was first recognised in statute with the implementation of the Historic Places Act in 1954. In 1987 the Act came under the jurisdiction of the DOC, again linking cultural and natural heritage. The NZHPT has been criticised for its colonial heritage focus, the DOC for its attention to natural heritage at the expense of historic heritage. A major finding of the PCE Report (1996a) was the loss of Maori heritage and the inadequacy of the current system to manage and protect Maori cultural heritage appropriately. This is likely to be representative of a historic and cultural heritage management system dominated by Pakeha. It illustrates the need to procure Maori involvement in places of significance to Maori.

This chapter has demonstrated that legislation is reflective of changing ideological values. The system of government has undergone significant change. Through the Town and Country Planning Acts and the Local Government Acts decision making power has been increasingly devolved. It has reached a point where, in theory, local communities through the current planning regime are given the opportunity to make a greater contribution to the way their districts are managed. This has wide-ranging implications for the management and protection of historic heritage. There is clearly a requirement for community level recognition of historic heritage values. If communities can perceive the benefits of preserving their historic heritage, protection measures will be implemented at a local level. Currently the RMA is the principal tool guiding local authority management of resources. The ways in which the RMA can be applied and appropriate mechanisms available to other historic heritage management agencies and the community are discussed in the following chapter.

Despite efforts made by heritage management institutions and legislators archaeological sites continue to be destroyed, and consequentially information is lost. In the past the focus on archaeological information recovery came from universities and museums. Today the majority of the excavation work is carried out in a resource management capacity, with local authorities and independent consultants now operating at the forefront. The following chapter explores the legislative framework responsible for the developing historic heritage management industry within which archaeological resource management operates today. It appears that New Zealand has further to progress before the legislation and organisations will be adequately able to protect and manage archaeological sites. It has only been in the past five years that the system has been reviewed, the results of which may not be evident for some time.