Difference between revisions of "Beyond the Scene"

(→Beyond the Scene - Landscape and Identity in Aotearoa New Zealand) |

|||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

'''Mini Review''' | '''Mini Review''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| | ||

| + | |{{Pop}} | ||

| + | |} | ||

Revision as of 15:50, 20 September 2010

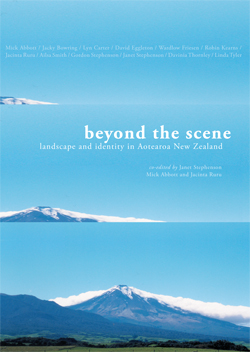

Beyond the Scene - Landscape and Identity in Aotearoa New Zealand

Otago University Press, 2010 Paperback, 224pISBN 9781877372810

Co-editors: Janet Stephenson, Mick Abbott, Jacinta Ruru

The Blurb:

What contribution does landscape make to our sense of identity? Images of spectacular natural features pervade the media – between the pages of glossy coffee-table books, in tourism promotions and on screen as the setting for blockbuster movies – but are these scenes that define its people?

For Beyond the Scene the editors asked eleven writers to choose a landscape that was important to them and to write it from the perspective of their life experience and knowledge. From farmer to art historian and film critic, geographer and planner to lawyer, from landscape architect to poet and environmentalist – these are diverse voices. Each discusses a very different landscape: from suburban Auckland and rural Waikato to a planned town in Canterbury and much-filmed Otago. Together, they investigate the relationship landscape has to identity, community and psyche.

Mini Review

This is a POP page.

|

The twelve contributors to this volume explore the meanings place has to them individually or the society resident in that place. The overall impression from these is just how varied that can be, for while there is only a little of parallel views of the same place it is clear that place is a very individual perception. The title of the book of course indicates that the intention is to go beyond place to landscape. The contributions are very varied from comparisons of very different Auckland communities, the historic landscapes of coastal Otago, created landscapes from new developments and even poetry.

Most of the contributors have a surprisingly narrow view of the landscape. The exception remarkably is a first generation New Zealander who is deeply engaged in learning about and contributing to his south Waikato landscape. He does, but few others seem to appreciate the geological underlay to New Zealand landscape. In a country where the geological bones poke through the skin so often and clearly, this lack of appreciation is remarkable.

Archaeology and archaeological sites for the most part get passing mention. There is no contribution by an archaeologist. Have our views of archaeological landscapes been so prosaic that no one stood out to contribute?

The contribution that directly uses archaeological material is that of Lyn Carter who considers South Island rock art, noting that few of the modern Ngai Tahu diaspora have ever seen the original art or are likely to, yet its iconography – usually repackaged - is very important to identity. The images have of course been much abused and some modern use even by the iwi seems less about legitimate development of an art, drawing on the style than about reinforcing identity. One can see here why cultural property is an issue to Ngai Tahu.

The Historic Places seminar on historic landscapes of a few years ago is frequently cited but historic landscapes are not the centre of this book. Rather the effect is to raise what a flexible construct an historic landscape can be when it is in the hands of the community, rather than a heritage expert. For that reason the book is a worthwhile read for anyone involved in historic heritage.